In the year 1966, Star Trek debuted, gas was 32 cents per gallon (wouldn’t that be nice…), the Vietnam War (and accompanying protests) was in full swing, and a small crew of scientists was on an oceanography expedition off the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia, almost to Bermuda. This crew was made up of members from the Duke University Marine Lab, lead by Dr. Robert Menzies. They were on board the Eastward– a boat designed specifically for oceanography expeditions such as this. On a clear and very chilly day in January, Menzies decided to drop a net into the ocean and await the treasures it would hopefully bring back up with it. One of these treasures, a crown jelly (Atolla wyvillei), made its way into our collection and allowed us to journey back in time for a day as we tried to better understand its story.

Dr. Robert Menzies began his career with an expedition to Baja California, Mexico in 1941, and continued actively pursuing oceanography expeditions around the world until his death in 1976. From our research, we found that he was considered an expert on isopods and described countless species of them. Throughout his career he studied and/or worked everywhere from Arizona State College and the University of Nebraska to the Allen Hancock Foundation and the Lasalle Foundation before making his way to the Duke Marine Lab. During his time at Duke University, Menzies worked as a professor of Zoology and served as the director of the Oceanography Program. This role is what lead him to be on the Eastward on January 19, 1966.

- Dr. Robert Menzies. Photo courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography Photographs.

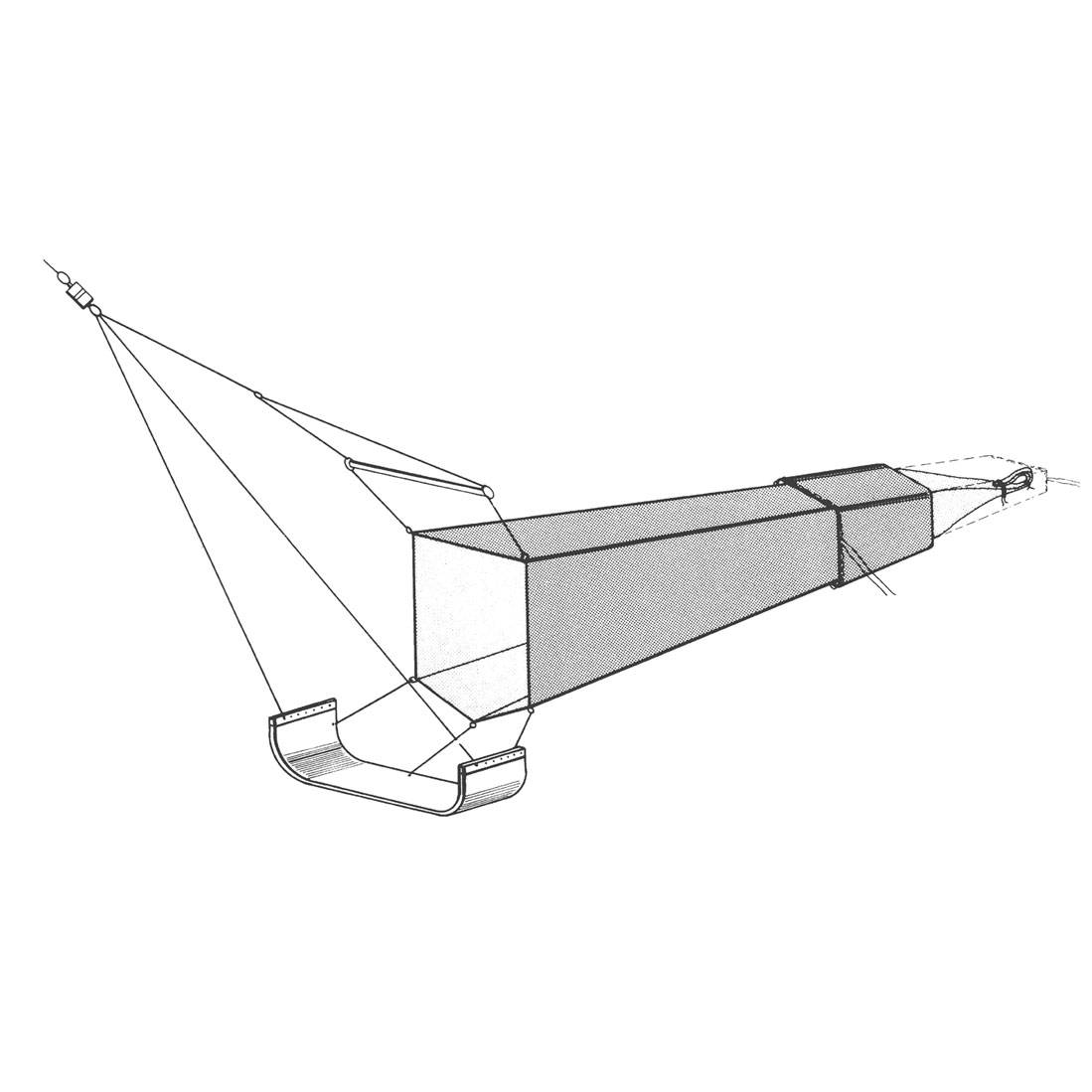

The specimen that Menzies collected that day and that caught our attention this week was Atolla wyvillei – a member of the order Coronatae, otherwise known as the crown jellies. The crown jellies fall under the class Scyphozoa which are considered the “true jellies” and the Phylum Cnidaria. Organisms within this phylum have stinging appendages called nematocysts and those of this class have no head, no skeleton, and no respiratory- or excretory-specific organs. According to the recorded distribution of Atolla wyvillei, these gelatinous organisms can live in the mesopelagic or bathypelagic regions of the ocean (200-3000 meters). Atolla wyvillei was originally described in 1880 by German naturalist Ernst Haeckel and the particular specimen that we are so fortunate to have in our collection was collected using an Isaacs-Kidd Midwater Trawl (IKMT). There is no telling how much came up in that net besides these 2 crown jellies that day. We can imagine an assortment of fauna and flora, but unfortunately we have nothing else in our collection from that day aboard the Eastward.

In our detective work we were able to find a lot of really awesome information, however, there is still a bit of mystery surrounding the crown jelly and the depth at which it was collected. In the jar that we inherited, one label reads a collection depth of 1500 meters, while another label reads 5300 meters. This is a pretty vast difference as you can imagine. So, there are a few possible scenarios that we have conjured up to potentially explain why there is such a difference in recorded depth.

The first of these scenarios is that there was some sort of transcription error over the past 52 years, which doesn’t seem too unlikely as this specimen went from the middle of the Atlantic to the Duke lab to multiple collections. We have no way of knowing for sure how many times this information was written and rewritten before it got to us. Another possibility is that the two labels indicate a range at which specimens were collected in the IKMT that day. We contacted a scientist with NOAA and her best guess was that 5300 meters was the depth at which the trawl stopped before collecting our crown jellyfish on its way back up. Which then begs the question, what is the significance of the “1500 meters” written on the accompanying label? A third scenario, is that the depth range at which this species of crown jellies can live is actually more vast than we thought, and this specimen is proof of that. Obviously to make any real claims, there would need to be extensive research and discussion with people who specialize in this subject. Who knows? Maybe someone reading this blog post has some answers for us…

No matter how many speculations we make, we have no way of knowing for certain what happened that day and at what depth these specimens were collected. Nevertheless, we can create a pretty spectacular image in our heads of what being on that boat on that day with Dr. Menzies and the rest of the crew may have felt like. Dr. Menzies was an amazing scientist and without his contributions- from his worldly expeditions to two tiny jellyfish in a collection in Raleigh, NC- there is no telling how different the field of oceanography would be. The Eastward was fascinating in and of itself. It was one of the first boats of its kind and it was used for numerous expeditions. So, you will likely hear about it again in future posts from us. We know it may be somewhat frustrating to some of you that there are still so many unknowns behind this jar of jellies, but that is also one of the things that makes science so amazing- the countless questions! For now, we will leave you with this little jar full of jellies- and it’s mysteries.

by Andie Woodson.

Thanks for reading our first Natural History Deep Dive! Please tell us what you think in the comments, and if you enjoyed what you read, share it with your friends and follow us on Instagram (@bwwilliamslab)!

Sources:

https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/auth_per_fbr_eacp22

http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=135282#notes

https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/findingaids/uamarlab/

https://sites.duke.edu/dumlphotoarchive/files/2014/04/DUML_News_v9_no1_Spring1991.pdf

https://books.google.com/books?id=kfv059OL6kQC&pg=PA336&lpg=PA336&dq=robert+menzies+eastward+duke+marine+laboratory&source=bl&ots=J6p2Gs_bcL&sig=ep5ls1bP-ZX4FEfe86MjCsOzYoc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi8uIqIhvfbAhUQP6wKHZwuCt4Q6AEINjAD#v=onepage&q=robert%20menzies%20eastward%20duke%20marine%20laboratory&f=false

A. bairdii or A. wyvillei? The label says the former and your text says the latter.

Good catch! The specimen was originally labeled as A. bairdii, but that is no longer an accepted species. So, the correct updated name is A. wyvillei. We wanted to show the original label to uphold some of the historical value of the specimen. Thanks for reading and commenting!!